3. Basic program structure and flow#

This chapter deals with basic program structure and some flow control. Flow control (switch etc) will be described in-depth in Flow control .

3.1. Basic program structure#

As stated before, a Java program must have a main() method as starting point.

This main() method needs to reside in a class, because all Java code needs to live inside a class.

This is the simplest possible app in

/**

* The package declaration; it defines the namespace of this class

* */

package snippets;

public class MostBasicApp {

/**

* This is a STATIC method, which means it is a class-level method and needs

* no object/instance to be callable.

* The return type is "void": it does not return anything.

* @param args the command-line arguments are passed here as string array

*/

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Basic App has started");

System.out.println("...and ended");

}

}

This is a very uninteresting app of course, since it doesn’t do anything. Let’s extend it with a bit of functionality. We’ll pass the program 2 arguments: one for age and one for user name. If no arguments are provided, we’ll print some usage information.

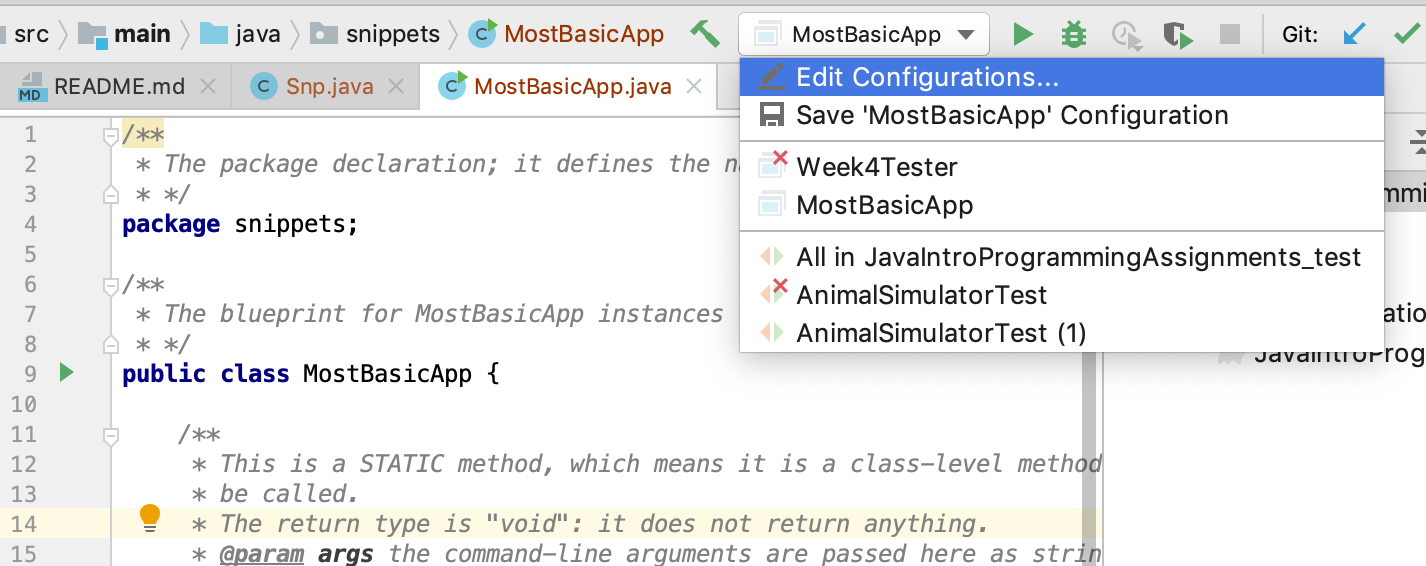

To pass command-line arguments within IntelliJ, you need to create or edit a run configuration. If you have run the main before (by clicking on the green triangle), you click on the toolbar run configurations box and select “Edit configurations”- see screenshot.

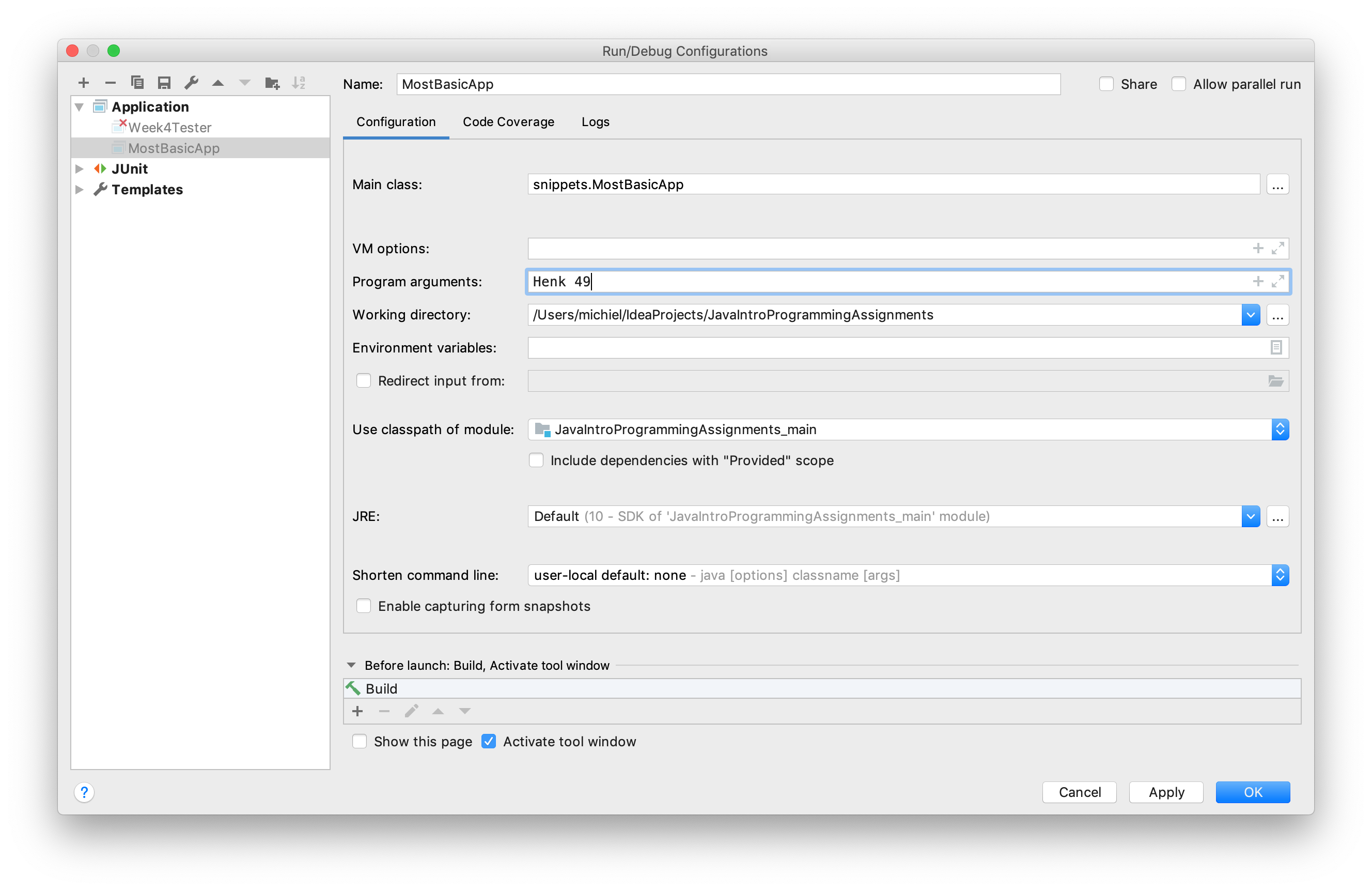

The only thing you need to do now is enter two “Program arguments”. Here, I filled out “Henk” and “49”, with a space between them.

An array (which is kind of a list) of String elements called args will be passed to main() as String[] args. This array will hold the command line arguments when next running the program, as demonstrated below.

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (String arg : args) {

System.out.println("arg = " + arg);

}

}

This will output

arg = Henk arg = 49

In a real terminal

In a real terminal you need to enter commandline arguments like this of course:

java -jar <my_app.jar> arg1 arg2

Here you have seen the first program flow control structure in action: the foreach loop. It is equivalent to for-loops in any programming language: it iterates a collection of some sort. Here the collection is an array. Note it does not have a counter variable; there is a different variant of the for loop for that.

Let’s introduce one other flow construct: decisions with if/else.

Suppose you want to give your user some uplifting message, depending on their age. First the age argument needs to be converted from String to int:

/**

* Use indexing to access array elements

*/

String name = args[0];

/**

* Parse String into int

*/

int age = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

System.out.println("Hi " + name + ", your age is " + age);

Warning

All commandline arguments -also the ones that may look like numbers- enter your program as String variables in a String array.

Next, the choice of message needs to be made.

if(age < 18) {

System.out.println("ahh the energy of youth");

} else if (age < 50) {

System.out.println("nice to meet somebody in the prime of their life!");

} else {

System.out.println("hey, don't worry - every day brings you closer to retirement");

}

These are the classic elements of the if/else decision block.

Finally, let’s bring a dedicated object into play: the message maker which will be responsible for serving messages based on the user age. The class looks like this:

package snippets;

public class MessageMaker {

private final String name;

private final int age;

/**

* Constructor makes it mandatory to instantiate with name and age arguments.

* @param name

* @param age

*/

public MessageMaker(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public void printMessage() {

System.out.println("Hi " + name + ", your age is " + age);

if(age < 18) {

System.out.println("ahh the energy of youth");

} else if (age < 50) {

System.out.println("nice to meet somebody in the prime of their life!");

} else {

System.out.println("hey, don't worry - every day brings you closer to retirement");

}

}

}

And this is how you instantiate and use an object of such a class.

public class MostBasicApp {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String name = args[0];

int age = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

/*A first object is instantiated and a method is called on it.*/

MessageMaker messageMaker = new MessageMaker(name, age);

messageMaker.printMessage();

}

}

So, here we have an application consisting of two custom classes. Both source files are in the same package (namespace). The first is the so-called “main class” which is the entry point of the application: MostBasicApp in source file MostBasicApp.java. The main method receives the command-line arguments and parses one of them into an integer. Next, it instantiates a MessageMaker object and calls its printMessage() method.

Create an executable

If you want to have an executable jar it needs two things:

A class with a

public static void main(String[] args)method signatureA manifest file in the jar with a reference to this main class; something like this:

Manifest-Version: 1.0 Main-Class: nl.bioinf.HelloWorld

This can be generated when creating the jar (using Gradle) if you include this fragment in

build.gradle:jar { manifest { attributes( 'Main-Class': 'nl.bioinf.HelloWorld' ) }

} ```

3.2. Summary#

You have seen the basic structure of a Java program. It needs at least one source file with one class. There needs to be a main() method of this signature to be executable as program:

public static void main(String[] args) {

//startup code

}

Two flow control structures were shown: the for-each loop and if/else decisions:

//foreach

for(item : collection) {

/*code block*/

}

//if/else

if(conditionIsTrue) {

/*code block for condition*/

}

else if(alternativeConditionIsTrue){

/*code block for alternative condition*/

}

else {

/*default logic*/

}