12. Interfaces & Abstract Classes#

So far, you have seen two basic types: primitives and classes. Classes have instance variables and methods acting on these. Here is an example.

public class Sequence {

String sequence;

String name;

/**

* returns the molecular weight, in Daltons

* @return weightInDaltons

*/

double getMolecularWeight() {

double weight = 0;

//implementation to calculate weight

return weight;

}

/**

* Mutates a single position and returns a modified copy.

* This object itself is NOT mutated!

* @param position

* @param newCharacter

* @return mutatedSequence

*/

Sequence mutate(int position, char newCharacter) {

StringBuilder stringBuilder = new StringBuilder(this.sequence);

stringBuilder.setCharAt(position, newCharacter);

Sequence mutatedSequence = new Sequence();

mutatedSequence.sequence = stringBuilder.toString();

return mutatedSequence;

}

}

So the contract (or API, if you like) of class Sequence is that it can deliver its molecular weight and can generate a mutated copy of itself. Both are concrete methods that are implemented with a method body.

Sometimes, however, you want to (partially) separate the contract from its implementation.

In Java, we have two separate constructs at our disposal for this. The first is te interface and the second is the abstract class. Both have their specific uses and disadvantages and these will be discussed below.

12.1. A contract without implementation: interface#

Maybe you remember from Python the print() method. It has this signature

print(*objects, sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False).

By default it writes to the console, sys.stdout, but you can change this

behavior as long as you pass an object with a write() method: print("foo", file=object_with_a_write_method).

Translating this to Java, which is strongly typed, the print() method would

expect an object of a certain type, or contract, exposing a write() method.

But since there are so many different ways to write() data (to console, to

database, to socket), it would be impossible to create a single implementation that

supports all possible ways to write data, now and in the future.

The solution is to define a contract without implementation, separating the contract from the implementation. Classes interested in fulfilling the contract can sign up and define their own implementation, as long as the contract is followed to the letter. In Java, these contracts are called interfaces. Staying with the Python print() function, we would have to define a contract (interface) defining a “write” method that states “give me your object and I will write it (to a destination of my choice)”:

Definition

An interface is a class definition with only abstract methods - they have no method body.

Interfaces usually define some behaviour that can be added to existing classes.

(Since Java 8, default implementations and static methods are also allowed. These are methods that do have an implementation, but these can never be dependent on any instance variables.)

Why is this useful? Let’s move away from simple printing a bit. Suppose we have a SequenceCollection class that

exposes a flush() method, that is supposed to write the held collection

to an external location for storage and clear memory to be ready for

filling: A typical case of batch processing. But the

SequenceCollection class does not know which storage technology is

preferred by its clients (API programmers), so it only asks API programmers

to provide it with an object implementing the SequenceWriter contract.

First, here is the SequenceWriter interface.

package snippets.apis;

public interface SequenceWriter {

/**

* This is the sole method defined in this interface. It accepts an

* object and will store a representation of it to an external destination.

* @param sequence the sequence to store

*/

void store(Sequence sequence); //NO METHOD BODY; ONLY A SIGNATURE!

}

The store() method does not have a method body - it only serves as a contract.

Here is the SequenceCollection class the “talks to” only the contract - it has no clue what kind of implementation it receives.

package snippets.apis;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class SequenceCollection{

private List<Sequence> sequences = new ArrayList<>();

public void addSequence(Sequence sequence) {

this.sequences.add(sequence);

}

public void removeSequence(Sequence sequence) {

this.sequences.remove(sequence);

}

/**

* This will write the current SequenceCollection to an external destination

* and empty the collection to be filled with a next batch.

* @param writer the writer that processes each individual sequence object

*/

public void flush(SequenceWriter writer) {

for (Sequence seq : this.sequences) {

//NO CLUE OF THE ACTUAL STORAGE IMPLEMENTATION

//ONLY KNOWS THERE IS AN OBJECT LIVING UP TO TO THE CONTRACT

writer.store(seq);

}

this.sequences.clear();

}

/**

* Looks for pathogenic sequences in the current batch

* @return pathogenicSequences

*/

public List<Sequence> findPathogenicSequences() {

ArrayList<Sequence> pathogenics = new ArrayList<>();

//complex logic

return pathogenics;

}

//MORE LOGIC INVOLVING THIS SEQUENCE COLLECTION

}

So now, if we want to use this SequenceCollection class, we need to provide it with an implementer of the contract. Here are two.

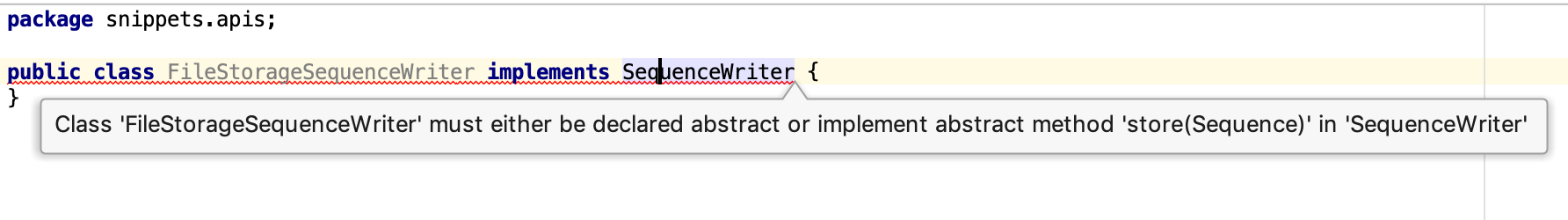

When you create a class in IntelliJ, and type implements SequenceWriter, you get a compile error, saying “Class X must either …. or implement method Y”:

Place the cursor on the line with the class name, press alt + Enter and select “Implement methods”. Select store() and press Enter. Boilerplate code has been generated.

This implementation simply lets the sequence get garbage collected.

package snippets.apis;

public class NoStorageSequenceWriter implements SequenceWriter {

@Override

public void store(Sequence sequence) {

System.out.println("not interested in sequence " + sequence.name + " anymore");

}

}

This implementation stores the sequence as Fasta to file (we’ll deal with file IO later so don’t be scared by that bit).

package snippets.apis;

import java.io.BufferedWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.nio.charset.Charset;

import java.nio.file.Files;

import java.nio.file.Path;

import java.nio.file.Paths;

public class FileStorageSequenceWriter implements SequenceWriter {

@Override

public void store(Sequence sequence) {

Path file = Paths.get("/Users/michiel/Desktop/finished_sequences.fa");

try {

if (! Files.exists(file)) {

Files.createFile(file);

}

String fasta = ">" + sequence.name + System.lineSeparator() + sequence.sequence + System.lineSeparator();

Files.write(

file,

fasta.getBytes(),

StandardOpenOption.APPEND);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

And here is the Sequencer class showing the usage of two SequenceWriter implementations:

package snippets.apis;

public class Sequencer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Sequencer sequencer = new Sequencer();

sequencer.start();

}

private void start() {

SequenceCollection sequenceCollection = new SequenceCollection();

Sequence seq;

seq = new Sequence();

seq.name = "harmless";

seq.sequence = "GATAACAGCATAGCAAG";

sequenceCollection.addSequence(seq);

seq = new Sequence();

seq.name = "probably harmless";

seq.sequence = "GATCAGCAACTCAGCACTACGGCT";

sequenceCollection.addSequence(seq);

seq = new Sequence();

seq.name = "really deadly";

seq.sequence = "GACACGCGCGCTACAGCACT";

sequenceCollection.addSequence(seq);

sequenceCollection.findPathogenicSequences();

sequenceCollection.flush(new NoStorageSequenceWriter());

// sequenceCollection.flush(new FileStorageSequenceWriter());

}

}

outputs

not interested in sequence harmless anymore not interested in sequence probably harmless anymore not interested in sequence really deadly anymore

while this

// sequenceCollection.flush(new NoStorageSequenceWriter());

sequenceCollection.flush(new FileStorageSequenceWriter());

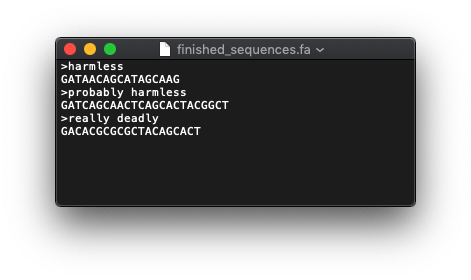

creates a file on my Desktop with this contents:

12.2. Abstract classes#

The second place where you can find abstract methods is in abstract classes. These are regular classes that are marked with the abstract keyword. The consequence of this is that they can not be instantiated directly; only concrete subclasses can be instantiated.

Definition

An abstract class is a class hat is marked with the abstract keyword.

It cannot be instantiated; only classes derived from it (i.e. subclasses) can be instantiated.

An abstract class may have abstract methods, but this is not required.

A major difference between abstract classes and interfaces is that classes can implement many interfaces, but can extend only a single one; Java does not allow multiple inheritance.

To stick with sequences, here is an example of typical usage of an abstract base class.

abstract class NucleicAcidSequence{

protected String sequence;

protected String name;

public NucleicAcidSequence(String sequence, String name) {

this.sequence = sequence;

this.name = name;

}

//getters omitted

//no setters provided!

public abstract char getComplementCharacter(char c);

public DNASequence complement() {

StringBuilder newSequence = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < sequence.length(); i++) {

newSequence.append(getComplementCharacter(sequence.charAt(i)));

}

return new DNASequence(newSequence.toString(), name);

}

public NucleicAcidSequence reverse() {

String newSeq = new StringBuilder(sequence).reverse().toString();

if (this instanceof DNASequence)

return new DNASequence(newSeq, name);

else if (this instanceof RNASequence)

return new RNASequence(newSeq, name);

else

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unknown sequence type");

}

public NucleicAcidSequence reverseComplement(){

return complement().reverse();

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return getClass().getSimpleName() + " (" + name + "): " + sequence;

}

}

Class NucleicAcidSequence is completely implemented except for one detail that needs to be implemented by its subclasses, DNA and RNA: public abstract char getComplementCharacter(char c);. Since this class defines an abstract method, it is required to be declared abstract itself.

Note this solution for reverse() is not general-purpose; you will need introspection for a more sophisticated solution. I chose this approach to enable chaining of method calls: complement().reverse()

Now, whenever a concrete (i.e. non-abstract) derived class (subclass) is defined, it must also implement (Override) this abstract method. Here is the DNASequence class:

class DNASequence extends NucleicAcidSequence{

static Map<Character, Character> complements = new HashMap<>();

static {

complements.put('A', 'T');

complements.put('T', 'A');

complements.put('C', 'G');

complements.put('G', 'C');

}

public DNASequence(String sequence, String name) {

super(sequence, name);

}

@Override

public char getComplementCharacter(char c) {

return complements.get(c);

}

}

Now, whenever you try this:

NucleicAcidSequence nas = new NucleicAcidSequence("ATCG", "generic sequence");

You get the compile error 'NucleicAcidSequence' is abstract; cannot be instantiated.

Here is some demo test code:

@Test

void testSequenceCreation() {

DNASequence dna = new DNASequence("GAATACCAGAT", "dna");

System.out.println(dna.complement().reverse());

System.out.println(dna.reverseComplement());

}

DNASequence (dna): ATCTGGTATTC DNASequence (dna): ATCTGGTATTC

12.3. These are the key players in Polymorphism#

Polymorphism is a term that comes from biology. It means “taking many forms”.

In object-oriented design, it is used to refer to the fact that implementers of interfaces, or extensions of (abstract) classes can show different behaviours with the same contract. You have seen it at work with the SequenceWriter interface that has two very sidtinct ways of being implemented, while the method call and reference type is exactly the same:

seq = new Sequence();

seq.name = "harmless";

seq.sequence = "GATAACAGCATAGCAAG";

SequenceWriter writer1 = new NoStorageSequenceWriter();

SequenceWriter writer2 = new FileStorageSequenceWriter();

List<SequenceWriter> writers = List.of(writer1, writer2);

for (SequenceWriter writer : writers) {

writer.store(seq); //two very different behaviours under the same contract

}

Definition

Polymorphism is the use of a single symbol to represent multiple different types

Interfaces make it possible to define a contract or API in a way that makes it possible to deal with an object as being of the contract type, without knowing its implementation, and without using inheritance.